“When I talk about climate change with people, I spend hardly any time on the science of climate change,” says Katharine Hayhoe, a leading climate science communicator and a speaker at Starmus Earth: The Future of Our Home Planet. The festival is almost here, and we’re delighted to publish an extensive interview with Dr. Hayhoe to explore issues ranging from effective science communication, “planet-hacking” efforts, to why science and faith are not at odds with each other.

Climate Scientist – Distinguished Professor at Texas Tech University – Chief Scientist for The Nature Conservancy

Katharine Hayhoe is an atmospheric scientist who studies how climate change impacts us and how we can effectively respond. She is globally recognized as a United Nations Champion of the Earth and an Oxfam Sister of the Planet, and has been named to TIME’s 100 Most Influential People, Foreign Policy’s 100 Leading Global Thinkers, and FORTUNE’s World’s Greatest Leaders.

Katharine is known for her ability to translate complex climate issues into accessible public discourse. She publishes a weekly Talking Climate newsletter, hosted the PBS Digital Series, Global Weirding, and writes for broad range of outlets, from TIME to Good Housekeeping. Her TED talk, “The most important thing you can do to fight climate change: talk about it” has more than 4 million views and her most recent book is “Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World.”

Currently, she is the Chief Scientist for The Nature Conservancy and holds the positions of Horn Distinguished Professor and the Political Science Endowed Professor in Public Policy and Public Law at Texas Tech University. Katharine earned her B.Sc. in Physics from the University of Toronto and her M.S. and Ph.D. in Atmospheric Science from the University of Illinois. She is a fellow of the American Geophysical Union, the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, the Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society, and the American Scientific Affiliation, and serves on advisory boards for organizations such as Netflix, UBS, and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. In recognition of her contributions to science communication and engagement, she has received a number of awards and four honorary doctorates.

WeLiveSecurity: You’re an award-winning atmospheric scientist who has also earned recognition as a leading communicator of climate science. You’re very active on many different social media platforms, from LinkedIn to BlueSky, and have your own newsletter on Substack, to name just a few platforms where you share your thoughts. How can scientists use social media and other modern ways of engaging with the public to get them interested and trusting in science?

Katharine Hayhoe: We live in an era where information can travel around the world almost instantaneously, allowing us to connect directly with others—including scientific experts—in ways previously unimaginable. Today, anyone with an internet connection can watch top scientists on YouTube or engage with them on micro-blogging sites like Threads, BlueSky, or X. These platforms enable scientists to share their passion and curiosity, sparking interest in science among young people who might not have considered it otherwise, and fostering a more informed and science-literate society in general.

Social media also offers significant benefits to scientists. By connecting with peers online, I stay up to date with the latest discoveries and have formed many positive professional and collaborative relationships. I’ve learned first-hand how engaging directly with people enhances my communication skills and teaches me what people most want to know about climate change, my area of expertise. And consistent with studies such as this, regular interactions with a diverse range of voices have also deepened my understanding of the disproportionate and often unfair impacts of climate change on those least responsible for it.

While social media can serve as a force for good, however, it also has the potential to harm. Sadly, research shows that misinformation is much more popular on these platforms than truth. One study, for example, found that false news spreads six times faster on Twitter than accurate information. Another quantified YouTube’s pivotal role in promoting flat-earth theories. Even platforms like TikTok, which have tried to ban climate disinformation, are finding it to be harder than anticipated.

When it comes to climate change and other scientific issues that have been deliberately politicized, like vaccines and masking, it’s essential to recognize that most of the negative comments and trolling we see online come from a small, vocal minority, supplemented by bot accounts. These detractors are not on social media to engage constructively or to be swayed; their aim is to consume your time, discourage you, and drown out your voice. So my advice to fellow scientists is straightforward: do not engage with trolls. Just block them. Save your time and effort for those genuinely interested; in my case, that means the many who want to better understand the urgency of the climate crisis and explore actionable solutions. They may not be as loud, but they are the majority!

On that note, another interesting remark you’ve made is, “How do you talk to someone who doesn’t believe in climate change? Not by rehashing the same data and facts we’ve been discussing for years”. So, how do you get someone who says that we can’t possibly know that humans are causing climate change or believes other pernicious climate change myths to listen to you?

To effectively communicate with those who disagree with us, it’s crucial to understand their reasons for disagreement. On climate change, many objections are cloaked in pseudo-scientific language, citing natural cycles or volcanic activity as causes or arguing that carbon dioxide is beneficial for life. However, the very basic physics that explains how humans are changing climate is the same physics that explains how stoves heat food and how airplanes fly; and no one claims those don’t work.

So why do people reject the science of climate change? Studies have shown it’s not because of any lack of education or intelligence. Rather, their social network or ideology has convinced them that the solutions pose a direct threat to their identity or their way of life. To support their perspective, they engage in motivated reasoning; not to determine whether it is right or not, but rather to justify what they believe. But don’t be deceived: the science-y sounding objections are just an excuse that allows them to reject the need for solutions. “If it’s not a problem,” so the logic goes, “then we don’t need to do anything about it.” That’s why “rehashing the same data and facts” by itself rarely effects long-term change.

A small segment of the population, about 10% in the US and slightly less in Canada, the UK and the EU, feel so threatened by climate solutions – sometimes even invoking visions of a one-world government imposing world-wide communism or a global earth-worshipping religion led by the Antichrist on every inhabitant of the earth – that they are what social scientists at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication refer to as dismissives. For them, rejecting climate solutions is integral to their identity. They ignore the consensus of centuries of scientific research and the findings of countless studies. Engaging with this group is rarely productive, as their views are deeply entrenched. When speaking to a dismissive, I often simply say, “I’m sorry, you’re wrong: now let’s talk about something else.”

For the majority, however, conversations can be transformative. Many who are doubtful or cautious don’t see the personal relevance of climate change and have been led to believe there are no viable solutions. Even larger numbers of people are worried but inactive. They feel helpless and hopeless, and don’t know what to do; so they do little to nothing, and they don’t want to talk about it.

What do people who are worried, concerned, or doubtful most need to know? First, they need to see how climate change impacts their personal world—the people, places, and things they love. I call this the “head to heart” connection. We hear the dire news about melting ice sheets and rising temperatures but until our heart is engaged, we won’t understand the need to act. Second, people need a sense of efficacy. Most people are worried about climate change, but have no idea what they can do about it.

That’s why, in my communications such as my weekly newsletter, I focus on explaining climate impacts in ways that are directly relevant to people’s lives, from our health to our food, and I always include information on actionable solutions. This approach empowers individuals to take meaningful actions, both personally and systemically, to drive change.

Early into one of his books, academic Tom Nichols says, “Never have so many people had access to so much knowledge, and yet been so resistant to learning anything”. Why is it that the public’s trust in science seems to have been decreasing in recent years. Are we doomed? How do you remain hopeful?

Trust in science often hinges on whether people perceive the implications of that science to threaten their lives and identities. For example, the complex and evolving science of dark matter rarely faces public skepticism, and it’s uncommon for those who study it to be the target of ad hominem attacks. The basic science of climate change, on the other hand, that explains how burning fossil fuels produces heat-trapping gases that warm the planet, has been well understood for nearly two centuries. Yet, it is often publicly contested and scientists who study it, accused of venality and more. This isn’t due to any legitimate doubts about the scientific basis for climate science, but rather because of the implications it holds for individual and societal decisions.

That’s why, when I talk about climate change with people, I spend hardly any time on the science of climate change, even though that’s my primary research field. (In my book, Saving Us, there’s only one chapter on it!) Instead, I emphasize how climate change affects our everyday lives. This may range from discussing the economic and health costs of fossil fuels, including their role in driving inflation and the impact of gas stoves on childhood asthma, to explaining how climate change is exacerbating weather extremes around the world, from heatwaves and droughts to floods and storms, and the impact they’re having on the safety of our homes, the quality of the air we breathe, and even our insurance rates.

Social science also shows that while doom-filled headlines garner the most clicks and shares, they are often ineffective at motivating action. That’s why I also spend a lot of time talking about what does catalyze action: namely, positive updates on climate solutions, stories of people and organizations making a difference, and ways everyone can catalyze change where we live, work, or study. My aim is to leave people feeling empowered and motivated to act—and based on some of the data I’ve collected, I think that’s possible.

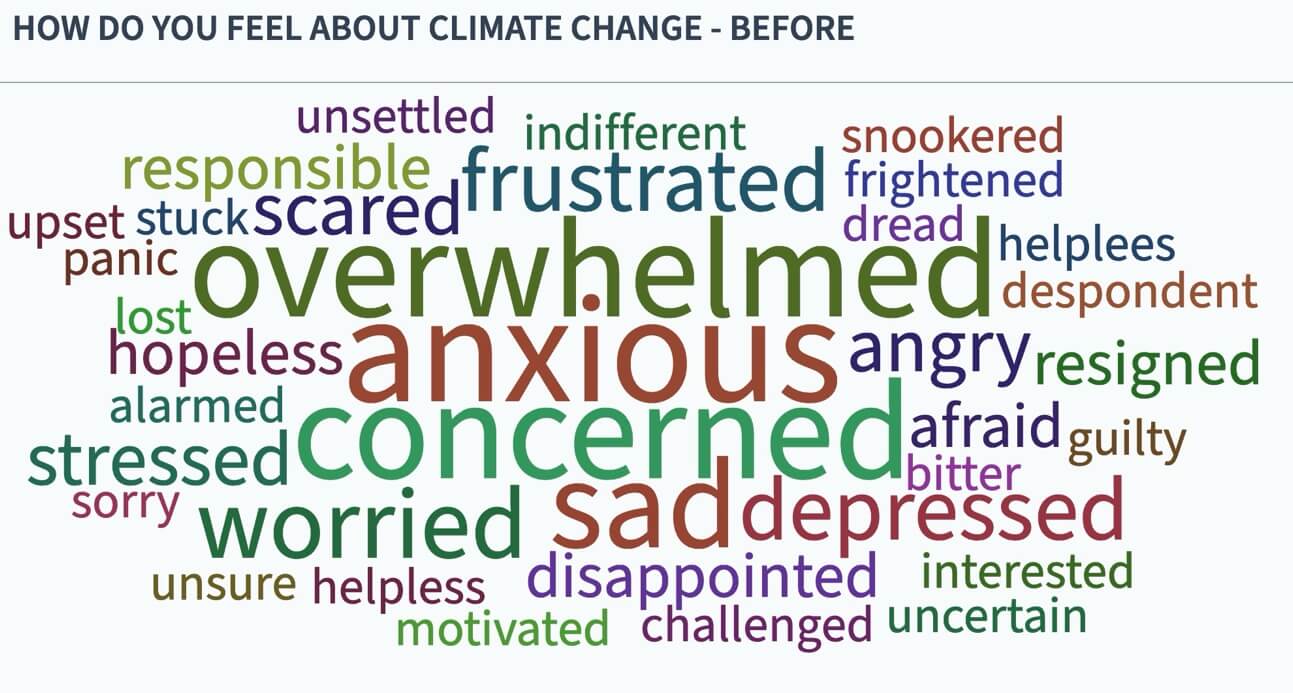

During my presentations, whether in person or online, I often start by asking participants how they feel about climate change. Their initial responses typically reflect concern and apprehension, as shown in the top figure below, with answers such as “overwhelmed,” “anxious,” and “sad.” At the end, I ask them the same question again. And as you can see in the bottom figure, many attitudes shift to “empowered,” “activated,” and “hopeful.”

Of course, many still feel worried and anxious – and that means we understand the scale of the problem. I’m a climate scientist, and I often feel that way myself. But what’s most crucial is that we understand how to channel this worry into action. And for that, we need a clear vision of a better future and what we need to do to get there. That’s what I call hope.

One of the first things people will spot on your website is “Hi. I’m a climate scientist.” along with a few images that contain a succinct summary of your work and mission. This includes the fact that you are an evangelical Christian, which some might say isn’t compatible with your day job. Why is such a dichotomy false and why are science and faith not in conflict with each other?

Many renowned scientists of the past, from Isaac Newton to Gregor Mendel, were known for their faith. Even today, research indicates that 70% of scientists at top U.S. research institutions consider themselves to be spiritual, with 50% identifying with a specific religious tradition. As a Christian myself, I view science as the study of God’s creation; so how could our scientific discoveries possibly conflict with our faith?

If that’s the case, though, then what’s the origin of the idea that science and faith are in conflict? On a personal level, there can be many reasons to reject faith. For some it’s a matter of culture influences, struggles to reconcile religious teachings with personal suffering, or disillusionment due to harmful experiences within religious institutions. On a societal level, however, historical conflicts between science and faith, from the time of Galileo to modern climate debates, reveal that the perceived conflict often arises from political and ideological motivations rather than inherent contradictions between science and faith.

As I discussed above, some see the solutions to climate change as posing a greater threat to their way of life, economic well-being, and the power structures they currently enjoy in our society than the impacts do. As a result, they often take advantage of the well-developed perception of a conflict between science and faith to discredit the science, with politicians opposed to climate action making claims such as “Climate change isn’t science, it’s religion,” or “The arrogance of people to think that we, human beings, would be able to change what God is doing in the climate is to me outrageous.” This often leads to profound misunderstandings, such as the idea that Christian doctrine is somehow opposed to climate action. In fact, I (and many others) believe exactly the opposite!

The reason I’m a climate scientist is because I’m a Christian. Climate change affects us all, but it doesn’t affect us all equally. Those most impacted are often the most vulnerable and marginalized, whether in our own communities or in regions like sub-Saharan Africa, the ones least responsible for creating this crisis in the first place. This injustice is what compels me to advocate so passionately for climate action: and I’m not alone. Many religious leaders, including Pope Francis and Patriarch Bartholomew, and organizations from the National Association of Evangelicals to Tearfund, speak out boldly and often on the moral imperative to address climate change. As Jesus himself told his disciples, his followers should be recognized by their love for others. And what is climate change, at its core, other than a failure to love?

Let’s now touch on the technology side of things. What is your take on viewpoints that reject technological solutions for addressing environmental issues, favoring strategies like degrowth instead? Another oft-touted way of limiting global warming to below 2°C (and ideally, 1.5°C) relative to pre-industrial levels involves tinkering with the atmosphere by deploying geoengineering and negative emissions technologies. Would the benefits of this last-ditch, “planet-hacking” response to climate change, once deployed on a large scale, outweigh the risks?

There is no single remedy for climate change that can solve the crisis on its own—and we can’t afford to wait for one. The good news, however, is that we have a multitude of solutions that can and should be implemented at every level, from individual to global. On their own, none are sufficient; but together, they offer more than enough potential to meet the global targets of the Paris Agreement.

To understand the vast landscape of climate solutions, I feel it helps to picture the earth’s atmosphere as a swimming pool. The level of water in the pool represents the amount of heat-trapping gases in our atmosphere. Over much of human history on this planet, we had just enough naturally-occurring heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere to ensure the planet was habitable and hospitable. In pool terms, there was plenty of water to swim, but our toes could still touch the ground to keep us safe.

All too soon, though, we humans stuck a hose in the pool and began to add more water than would be there naturally. At first, the amount of water coming out of the hose was minimal, coming from the expansion of agriculture and associated deforestation. The Industrial Revolution, however, kicked it into overdrive and the amount of water coming out of the hose began to rise exponentially. The main driver of this increase was our growing reliance on coal, gas and oil for energy, with additional contributions from large-scale agriculture, deforestation, and other land use change.

READ NEXT: How space exploration benefits life on Earth: An interview with David Eicher

To fix the problem, we need to turn off the hose; and the science is clear that the faster we do so, the better off we’ll all be. We can accomplish nearly all of this through efficiency, clean energy, climate-smart agriculture and behavioral changes; and for the last few drops that are impossible to mitigate otherwise, we have expensive technological options such as carbon capture.

However, our pool also has a drain. By making the drain bigger, we can remove more water from the pool at the same time that we’re turning off the tap: up to a quarter of our present-day emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. We can make the drain bigger through protecting, restoring and regenerating ecosystems that take up and store carbon; through regenerative agricultural practices that build up carbon in the ground; and for the last few drops that can’t be achieved any other way, expensive and energy-intensive technological options (you see the pattern here) such as direct air capture.

There’s one more thing, though. For some, the water in the pool is already so high that their toes don’t touch the ground. That’s why we must also accelerate solutions for adaptation and resilience: solutions that help us grow more food, make clean water more abundant, ensure our homes and infrastructure are safe, and protect our health and that of the natural world’s, in a world that is already much warmer, with more frequent and damaging weather extremes.

We need to implement as many of these solutions as possible, as soon as possible – but we can’t do everything, everywhere. So how should we prioritize? Personally, I advocate for solutions that have multiple win-wins; climate actions that also address inequality, support local communities, enhance public health, and ensure access to food, clean water, and safe environments. This approach emphasizes the importance of actions such as improving energy efficiency, investing in clean energy worldwide, reducing food waste, adopting sustainable agricultural practices, building community-level resilience and conserving natural resources. Additionally, it highlights the risks associated with climate solutions that harm communities and ecosystems, such as siting renewable energy projects in sensitive habitats, placing blame on marginalized populations for high birth rates, and over-reliance on expensive and energy-intensive technological fixes or untested planetary-scale interventions such as solar radiation management.

We must begin with our current systems and the tools available to us today. Equitable and sustainable solutions that benefit both people and the planet are already at hand: and one of my favorite resources that helps us identify those solutions is Project Drawdown. Whether you’re looking for actions that can be taken by an organization, a company, a region or a person, there’s sure to be a few on their list that empower you to take action against climate change. However, by implementing these, we can begin to effect the societal changes needed to address not only climate change but many of the other crises, from biodiversity loss to inequity, that stand between us and a better future.

As we wrap up our conversation, are there any closing remarks you’d like to leave us with?

In the face of climate risks that threaten our planet’s stability and the well-being of current and future generations, the urgency for action has never been greater. We have the knowledge and the means: what we most lack is the collective will to implement effective climate solutions. Each of us has a part to play, from individuals making conscious choices in their daily lives to citizens advocating for systemic change to policymakers enacting bold initiatives on a global scale. As Jane Goodall says, speaking to each of us, “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

Our shared path forward demands courage, determination, and collaboration. It calls for us to rise above the fear and inertia that paralyzes us, and to realize the transformative potential of climate action. There’s no time to waste and if a sustainable and resilient future is truly possible, the only question I would ask you is – what are we waiting for?

Thank you for your time.